Lessons Through a Screen

For the past year, Eugene’s Bridgeway House has navigated through the ups and downs of teaching special education during a world-wide pandemic. Here’s how the school did it.

By Julia Page

Looking out at the faces and names that popped up on her computer screen, Akiko Kato welcomed each of her students with a smile and a “good morning.”

“A lot of us are having unstable internet today,” Kato said as she counted the number of participants in the day’s Zoom call. As Kato prepared to share her daily PowerPoint presentation, some students made small talk with one another while others sipped from their cups of tea or remained with their cameras off.

A few quick clicks and, suddenly, every student's screen became one of the same. Kato clicked to reveal the schedule for the day: individual math lessons first, a group “brain boost” exercise session, a few lessons on grammar, some group readings, a bit of time to learn a world language and a couple of 10-minute breaks here and there.

“I’ll see you all back here at 9:50,” Kato said as her students slowly disappeared into their individual breakout rooms. And with that, Bridgeway House’s Room 9 began its usual virtual routine.

Bridgeway House is a Eugene-based nonprofit organization specializing in treatments, programs, and therapies for children, teenagers and young adults with autism. Since its doors closed in March of 2020 due to the pandemic, students have adjusted to the virtual activities, routines and interactions that define online learning.

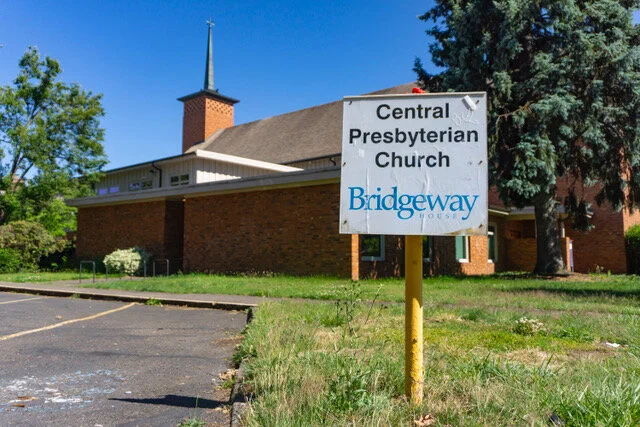

Bridgeway's main administration building on 15th Avenue is attached to Eugene's Central Presbyterian Church. After their summer school is over, which will continue to run on a modified schedule, Bridgeway plans to return to fully in-person instruction in the fall in accordance with CDC and Oregon guidelines.

Kato, the leading instructor for Room 9, has been a special education teacher at Bridgeway House since 2009. Originally a general education teacher in Japan, Kato, now 60, enrolled in the Special Education program at the University of Oregon shortly after moving to Eugene in 2006 with her husband, Phil.

“My parents were teachers, and I didn’t really want to become a teacher when I was very young,” said Kato. “But, as a woman, being a teacher was considered to be a very good occupation to become independent, and so that’s why I just fell into teaching, following my parents’ path.”

Despite her initial reluctance, Kato has been happily teaching for over 35 years. But unlike the previous 34 years of teaching students through hands-on, in-person learning, Kato, along with the other eight teachers employed by Bridgeway, has had to make drastic adjustments to her lesson plans over the past year.

In order to ensure that every student’s specific needs are met during their time in the special education system, teachers work and communicate with the student and their family to create an Individualized Education Program (IEP). For Kato’s class, whose students range from ages 13 to 20, these IEPs are especially important to make sure every student learns at their own pace. The switch to online learning made it even harder to follow these already complicated schedules.

“It was crazy: endless, endless research on learning management systems,” Kato said. “Endless webinars, trying to find the free resources and making the decision of which one to use. There are so many resources, websites, worksheets, sites and everything, but then you have to find the ones that would work for your students.”

The switch to solely virtual classes has been a learning curve for both students and teachers. The usual schedules that students at Bridgeway followed were seriously altered by the stay-at-home orders. “The unknown was and is so hard and unpredictable [for the students]. It’s all very different from their old routines,” Kato said.

For some Bridgeway students, transitioning to Zoom classes wasn’t a viable option to consider. Through a modified schedule and safety precautions at the school, a handful of students have been allowed to come to Bridgeway face-to-face lessons. “We do have some students that just aren’t capable of virtual learning, and we’re seeing them in person,” said Patricia Wigney, the executive director of Bridgeway House. “Some students have elected to just sit it out, and we do packets and mail packets for them.”

In Room 9, nine out of the 12 students in the class attend the Monday through Thursday virtual classes. The remaining three have remained in contact with Kato and Bridgeway but find it too difficult to navigate the Zoom meetings. As a result, they work independently on their classwork at home. “The unknown is so hard and not predictable. It’s all very different from their old routines,” Kato said.

For some students in Room 9, like TJ Cruden, 18, Zoom classes have been much easier for both students and teachers to navigate in comparison to in-person classrooms. “I think it’s much easier to learn on Zoom. It just takes a couple of clicks, not having to set up a projector or anything to get stuff on there,” Cruden said. “I think, in our own homes, we have much better internet connection compared to the Bridgeway House’s.”

Over the past 15 months, Akiko Kato, 60, has been virtually teaching her class at Bridgeway House from her own home through Zoom. Although classes are shorter than before the pandemic, online teaching has still been a full-time job.

“Some students are doing better online because if they want to have space to themselves, if they want to take a break then they can sort of mute the microphone and have their cameras turned off,” Kato said.

Nonetheless, after weeks and weeks of the online Zoom daily routine, the once foreign and unknown aspects of virtual learning have gotten easier for students like Jackson Wheeler, 16, to get accustomed to.

“I think I’ve gotten into a routine,” Wheeler said. “But it’s when one of those unexpected glitches happens that really sets it apart.” Some of the glitches that Wheeler has had to face include faulty headphones and the inability to connect to Zoom on his laptop. During one week in this school year, Wheeler had to attend his class through a smartphone.

Unlike typical in-person classes at Bridgeway, where students, teachers and instructional assistants intermingle in the same room, online classes have allowed instructors to separate their students into breakout rooms with little to no effort. “In that breakout room, I just click on it and just move them. I have all the control and power really quick,” Kato said. “Dealing with people in person, they missed that now, they really want the connection with the people, actual physical, in person, physical education. But then they did mention once that it's less destructive now; when they're put in the breakout room, it's quieter.”

After months of empty school desks and pixelated faces, most of Bridgeway House’s classrooms were able to restart in-person classes on April 12 with a modified part-time schedule. Now in Phase 3 of the reopening plan, where students return to school buildings for in-person learning, but classroom schedules are modified with decreased numbers, there is hope that life in the education world will soon return to normal.

For Kato’s Room 9, however, the decision was made to continue with virtual learning. “I’m not comfortable with getting out of the house now; there’s just so many things going on, too, that aren’t just COVID,” Kato said. “I am concerned since I’m not that young, and there’s so many unknown things and factors still.” In contrast to the rest of the classrooms, most of the students in Kato’s class are content with distance learning until things become even safer in Eugene. “Most of the students are doing the work online and they are getting the work done,” Kato said. “Parents are concerned still because not all students are vaccinated yet.” Room 9, which is a larger class than the rest of Bridgeway’s classes, would also be harder to maintain social distancing.

Although there are still many unknowns, Bridgeway House plans to end its Zoom classes when summer school begins in July and transition back to all in-person classes by this fall. Until then, classes like Room 9 will just keep on logging out of their virtual rooms one-by-one, smiling as they wave goodbye to their classmates' names and profile pictures.