On the basis of succesS

In the 50 years since the passage of Title IX, female athletes at the University of Oregon have made great strides.

They also know the game is not over.

written by SHANNON GOLDEN

photographed by SEREI HENDRIE and ISAAC WASSERMAN

In 1973, during her first year at the University of Oregon, Peg Rees says that the athletes on the nascent women’s volleyball, basketball and softball teams shared one set of uniforms. Rees, who played on all three teams, remembers that the uniforms were simply passed on to whichever team was in season.

Not until 1976, Rees’ junior year, did each team receive its own set. It had been four years since Title IX went into effect, and the university had begun addressing funding gaps between the men’s and women’s programs. “That was huge,” says Rees, 67. “But we still had to do our own laundry and wash them,” she adds, chuckling.

Gloria Mutiri, a junior on this year’s UO women’s volleyball team, has five sets of uniforms in varying combinations of green, yellow, white and black. After games last fall, Mutiri, 21, and her teammates simply left their uniforms in the locker room to be washed by team managers.

This transformation in Oregon’s women’s athletics didn’t happen overnight. It took years for the UO — and the country — to recognize what female student-athletes could achieve and build programs geared toward their success. This shift began in Congress in the early 1970s with the passage of Title IX.

June 23 will mark 50 years since Title IX was enacted. This clause of the Federal Education Amendments prohibited sex-based discrimination in any activity that receives federal financial assistance. In the half-century since Title IX went into effect, administrators and female athletes at the UO have worked to transform Oregon athletics from a threadbare program into one of national and global prominence.

Rees and Mutiri — along with three other pioneering athletes — reflect on their time at the UO. From the frustrating inequities to victories big and small, they tell their sides of the story. Although these five women were never teammates, they all shared a drive to succeed that overshadowed the many challenges in a decades-long fight for collegiate sports equity.

Rees now serves as a game caller and public-address announcer for the UO softball program.

1970

When Peg Rees was a kid growing up in Compton, California, after-school sports didn’t mean orange slices, carpools and agility drills around plastic cones. They meant playing “kick the can” and flag football on asphalt and front lawns. Rees says she was often turned away from opportunities to play on local sports teams because she was a girl.

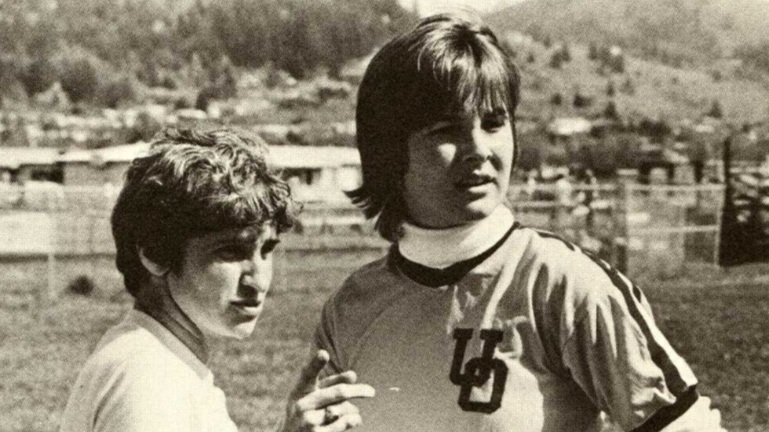

Peg Rees (right), a member of the UO volleyball, basketball and softball teams in the early 1970s.

In 1973, when Rees started college, she sought out every opportunity to compete. She joined volleyball, then basketball and softball. The programs were still only considered a part of the physical education department and received meager funding from the university.

“We were arguably the best women’s department in the United States,” Rees says. “But we had bare-bones facilities, coaching staff, budgets and resources.”

The first practice space for Oregon women’s softball was far from sufficient. The inaugural team practiced on the field behind the Main Library (now called Knight Library) — a sloped pitch with no infield or foul lines. A flimsy wire mesh backstop prevented foul balls from striking unsuspecting students walking to class.

“It was a place to throw and catch,” says Rees, who was a pitcher and catcher for the team. “But it wasn’t a place for really honing your skills, which is what you should be doing every day.”

By 1977 and the end of Rees’ college career, the Women’s Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics at Oregon had a budget that was one-thirteenth the size of the men’s athletic department budget. Still, small victories punctuated her time. In 1976, 10 of 11 women’s teams qualified for postseason play.

“Every once in a while, something would change to our benefit. It was encouraging. It was hopeful,” says Rees, who made it to three national Women’s College World Series with her teammates. “Even though I didn't personally experience a lot of the positive change, I could see it coming. There were glimpses of it along the way.”

1980

In 1974, the University’s Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics finally approved scholarships for female athletes based on individual need. With support from former coaches, basketball forward Bev Smith became one of the first female players at the UO to receive an athletic scholarship.

During Smith’s freshman year, 1978, the UO women’s basketball team celebrated its sixth official season with a different kind of win — university athletics gave the team full access to McArthur Court. The team was finally allowed to practice and play in the building the men’s teams had been using since 1927.

According to Smith, 61, there were still “huge discrepancies” between the men’s and women’s teams. The men received higher quality gear, including shoes and practice uniforms. Smith still commiserates with former teammates about the physical education department-issued cotton practice shorts that chafed their thighs. “Chub rub,” she calls it.

For Smith and her teammates, it didn’t matter what they wore to practice. It mattered that they had a space on campus to showcase their talent. “We were just trying to take advantage of the opportunity and the chance we were given to play in Mac Court or to have our own marquee,” says Smith, who led the team to 40 wins on the Ducks’ storied home court.

In 1979, Smith and her teammates played against the South Korean women’s national team, which was preparing for the 1979 World Championship. Over 5,000 people paid $1 to watch the game.

“The student section was awesome. They were down on the floor across from us on these old wooden bleachers that were pulled out,” Smith says. “When they would get stomping and yelling, it would just shake the whole court.” Oregon won the game by one point.

“Once we sort of established ourselves as a competitive team at the University of Oregon, I never looked back,” says Smith, who received her degree in 1988 and earned two All-American honors. In 1992 she was inducted into the UO’s Hall of Fame. “I just completely enjoyed the thrill of competing in collegiate athletics at that scale.”

Bev Smith wanted to see what else there was outside the world of basketball after her time in college and playing pro overseas in Europe. Eventually she found herself helping organize sports programs for the Eugene youth community.

1990

Title IX slowly increased scholarship opportunities and recruitment efforts for female student-athletes at universities across the country. For some lower-income students and students of color, their athletic abilities began to open doors for them in higher education.

After a record-setting high school career playing volleyball and basketball and running track, LaReina Starr received offers from several colleges. “I always wanted an athletic scholarship. I knew that was my avenue to getting to college,” says Starr, 49, who grew up in Corvallis, Oregon.

In 1991, Starr accepted a full scholarship to run for the UO track and field team and play on the volleyball team, becoming the first Black woman to play Division I volleyball for Oregon.

Having grown up in Oregon, Starr felt prepared for the predominantly white environment at the UO. She attributes her success to other pioneering women of color around the country, such as volleyball legends Flo Hyman, Tara Cross and Trisonya Thompson.

Starr says it wasn’t always easy being the only Black woman playing a predominantly white sport, yet she worked to find her space on campus. “My goals when I got to the UO were to be a part of something great and to leave it better than I found it,” Starr says. “To me, being one of those African-American females on that campus, I was going to let my light shine.”

By her senior year, Starr was the Pac-10 champion in the 100 meters and a member of UO’s 1600-meter All-American relay team. Rees was an assistant volleyball coach during Starr’s time at the UO, and the two formed a longstanding bond.

“She just made me believe I could do anything,” Starr says of Rees. “She stuck with me.”

It was in moments of community-building when Starr found her stride at the UO. She and some of her teammates often confided in each other about being women of color on campus. They worked together to fundraise for track meets and buy new uniforms.

“I always felt like the women’s teams outshined the men by just doing their work,” says Starr, who now coaches track and field and girls’ JV basketball at Portland’s Central Catholic High School. “We were getting the second best, but it never stopped us from dominating or doing what we did.”

Former Oregon athlete LaReina Starr shows off her school ring from 1996. One side of the ring represents her time as a track and field athlete, the other is dedicated to her time as a basketball player.

LaReina Starr returns to McArthur Court at the University of Oregon. Starr was a two-sport athlete at the UO, competing in volleyball and track and field.

2000

Louisa Dorsch lugged her heavy lacrosse bag with her each Shifting from club play to Division I competition was day to class. As a member of the UO club lacrosse team, she didn’t have a place on campus to store her goaltending equipment, so she carried her gear around until the team’s evening practices. “You’re basically a giant billboard of what sport you play when you have to do that,” she says jokingly.

Dorsch played on the club team throughout her time at the UO. In addition to her position as goaltender, she managed the team and ran practices. During Dorsch’s fourth year, the athletic department had taken note of the club team’s growing success. In 2004 it hired coaches for the first Division I women’s lacrosse team at the UO.

Dorsch (#29) prepares to pass in a game against Ohio University in 2005. The Maryland native played all 60 minutes of the game.

The new coaches attended a few of the club practices. Impressed by the players, they offered four students spots on the team. Dorsch made the cut. She decided to stay in school as a fifth-year senior and signed on as a member of the inaugural team — with a locker in the student-athletic center to store her equipment.

Shifting from club play to Division I competition was more intense than she expected. Dorsch said she and her teammates learned to embody the “intense work ethic” of student-athletes – excelling on and off the field. When she wasn’t going to class, Dorsch spent hours studying film from past games and practicing stick skills.

“To get to this top level of playing and even compete against these other amazing teams, it was really special,” she says.

Dorsch, who now teaches at Churchill High School in Eugene, spent only one year in Division I, but representing the UO on the field brought her a new sense of community. Despite being the newest team on campus, women’s lacrosse never felt second to the well-established programs, Dorsch says.

“That’s kind of the beauty of going to a big university,” she says. “Everyone can tether themselves to something and feel seen and valued.”

Former lacrosse player Louisa Dorsch works with the next generation of female athletes by coaching young girls in Eugene.

TODAY

For Gloria Mutiri, 21, the fight for sports equity at the UO looks different than her predecessors’. Mutiri and her volleyball teammates now play in million-dollar arenas and have access to state-of-the-art training resources. But their accomplishments on the court sometimes go unnoticed.

“Women’s sports are the fastest growing sports in the U.S. right now,” says Mutiri, a right-side hitter for the Ducks the past two seasons. “But if I turn on the TV, I would probably find a men’s basketball game.”

Female athletes have turned to social media to promote themselves as student-athletes. “I think that’s helped put some of the power back in the athletes’ hands,” Mutiri says.

Women of color are still underrepresented in the fight for collegiate sports equity, especially in coaching positions, Mutiri contends. “I’ve never had a Black coach in my life, or anyone who even looks like me be involved in my volleyball journey,” says Mutiri, who received the UO Black Student Union Female Athlete Award in March.

During club tournaments in high school, Mutiri’s teammates often wore matching hairstyles, complete with colored ribbons. For Mutiri, this camaraderie was often isolating. “I’m the only one with kinky 4C hair. I’m the one with braids in,” she says. “Those kinds of experiences can make you feel alienated even within a team.”

Last fall, Mutiri had green braids for the start of the Pac-12 season to show school spirit. She stepped out on the court for the first few games and noticed other Black players wearing braids that coordinated with their school colors. To her, it was empowering to see more Black female athletes in the Pac-12 who took pride in their teams.

“I’ll definitely never take this experience for granted,” says Mutiri, who plans to play volleyball professionally and pursue sportscasting after college. “Playing with strong women who know what they want and stick up for themselves and demand more from the UO and from the National Collegiate Athletic Association is really cool.”

Oregon’s Gloria Mutiri serves during a volleyball match against Cal at Matthew Knight Arena last fall.